A Contrastive Look into the Meaning of North Korean Paintings

By Will Boyd, PhD

A few years ago, I remember looking on in anticipation as a batch of paintings from several North Korean “National Treasures” artists, slowly slid from their protective coverings to form a small pyramid of scrolls on a white sheet spread out on my apartment floor. My best friend from college, Mike, brought them back to the US, partly as a gesture of good will and partly to show the American art community the unexpected serendipity of having a North Korean communicate over the gulf of ideology and politics that separates our two nations through the flimsy elements of water, soot, and rice paper. I don’t know what I was expecting, but as scroll after scroll was unfurled before me, the swirls of color and bold brush strokes seemed to catch me off balance and lodge in my mind’s eye in a profoundly simple expression of joy. A kind of joy unexpected from a land associated in the media with terror, famine, and deprivation. I had not expected to be moved by art from the most narrowly defined ideological genres in existence… instead I was overwhelmed.

I have studied Chinese painting for years, formally and informally, learning traditional calligraphy and dynastic forms to the place where I would recognize their influence anywhere. I am also as familiar with political art of both the Eastern Block and the Cultural Revolution of China, but what I saw spread before me was nothing like what I expected. I was looking for the broad-shouldered and scowling Moscow youth, or for the red backgrounds of Soviet expressionist painting to somehow mesh with the plum blossoms and cranes of traditional Goryo (Korean dynastic) painting, but what I beheld instead were the heroic vistas and landscapes of a fantastic and imaginary paradise, sterilized of all but the most remote human influences. Seeing that the North still claims that it is a “workers paradise”, and that humanitarian aid is only accepted out of respect for the countries wanting to give it, perhaps the idyllic landscapes and scenes of natural beauty are the result of a kind of inner utopian philosophy that grows out of severe introversion. But, for sure, I was not prepared for the kind of inner dialogue that these paintings would begin to my mind, and the kind of questions that they would raise about their creators, with no easy answers apparent or hinted.

A strange familiarity drew my eyes to the strong blues and grays of a painting of Mt. Baekdu, a volcanic lake to which both the Koreans and the Chinese lay claim, and the centerpiece of many myths regarding ancient Asian culture and an ancestral right to rule. I had seen many similar paintings in China, but none that sparkled like this one. The Korean people’s first king, Tangun, was born here, a descendant of heaven and a garlic-transformed she-bear; as was Kim Il Song, who is said to have inherited Tangun’s mantel of authority through direct descent and spiritual intuition. The Chinese believe that this volcanic crater is a fountain of youth, bringing about Taoist ascension and immortality. To some Chinese, this mountain is the center of an enormous Feng-Shui energy fountain, literally bathing the pilgrim to its shores in transformative powers of positive Qi. The Chinese historical attachment to this place resulted in cutting the mountain in half, along the China/DPRK boarder in a kind of “forced sharing”, and Koreans all over the world still lament over its unfairness. Equally idyllic portraits of Mt. Baekdu grace countless South Korean restaurant walls and government building, because its holy shores were supposedly the sight of the world’s first civilization, a perfect Korea that is said to outdate China’s birth by thousands of years. It is by these claims that Korea takes solace in centuries of colonialism and persecution, and the belief that Korean culture takes rightful historic precedence over both China and Japan, its traditional rivals. As I looked into the depths of this volcanic lake, it occurred to me that this was not painted as a picture, as revealed by the surreal heroism of its romanticized slopes, the shaded snow, and the steam raising off of its crystal-clear water, but was crafted as the ultimate symbol of what North Korea believes, the highest expression of its faith in nationalism, racial superiority, mythical history, and its incarnation in the form of their political leaders.

Our eyes moved next to the form of a tiger in tall grass, and for a few moments were locked in its gaze. I was immediately reminded of the Chinese theory that the first king of prehistoric China, the honored Yellow Emperor, incorporated the symbols of all the tribes he encountered, and after an excursion into the North, the Chinese began to use the motif of inter-coiled Dragon and Tiger for the first time, a symbol of the conflict that began between the agrarian peoples in the “Yellow Plateau” and the hunting cultures of the forested North, the ancestors of the Koreans. The Chinese believe that of all the mythical beasts, only the Tiger is mighty enough to resist the Dragon. The Koreans, too, have taken up the motif of the dragon, but the Tiger is found on everything from the embroidered frocks for the heirs of Chosun Dynasty court officials, clay toys made by farm hands, and flags painted for harvest festivals, to its highest development in Korean brush painting. Unlike many other forms that the Koreans copied from dynastic Chinese art, the Chinese copied the Tiger form from Korea. Again, I found the paintings spread before me to be unique commentary summing up the paradox of the Korean people as heavily associated with the Chinese continuum, yet adamantly opposed to being controlled or over-shadowed by the larger neighbor’s cultural impositions or expectations.

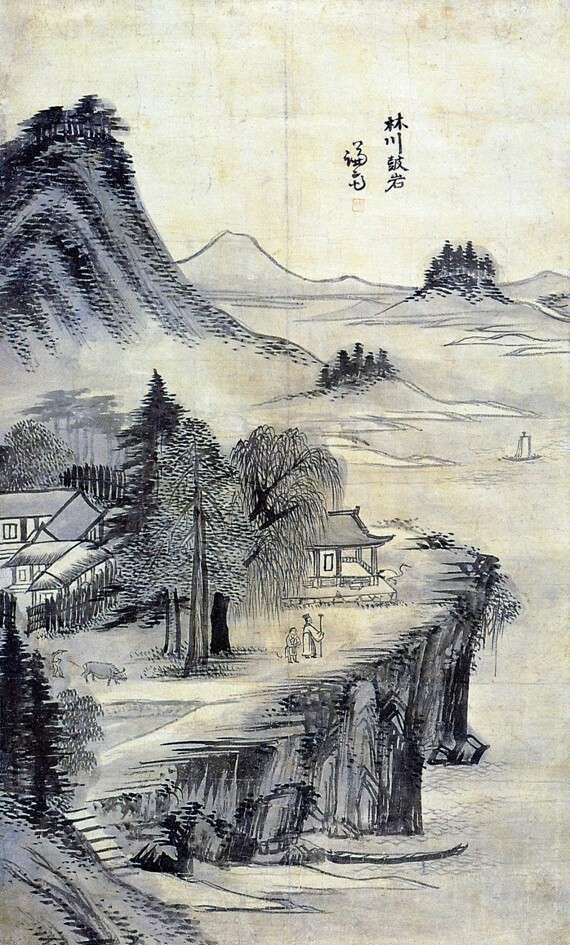

The North Korean landscapes that we slowly savored were monumental testimonies to man’s capacity for rapturous bliss and escape into the mysteries of nature. With random brush strokes and effortless spontaneity, the landscapes roll with the same kind of unanticipated grandeur that we see in the scenery of nature. But even more striking to me was their silent commentary on the human condition and a kind of romantic naturalism that spins into a kind of sterile utopianism, breaking with the last remnants of with Chinese brush painting tradition. While outwardly very similar to Northern Chinese landscape painting, the critical omission that makes these paintings remarkable stands out immediately – the total absence of the human form or implied human involvement. In traditional Chinese humanism and its outgrowths in modern Chinese political socialism, the landscape is seen as a stage for human endeavor and interaction. The land belongs to the government, and the people carve it to their revolutionary will. During Mao’s reign, landscapes were only approved for display if they properly set the workers and farmers in their industries and activities. Even the large traditional Chinese landscapes in my collection are dotted with cottages, palaces, boats, bridges, and the occasional two-dotted figure that represent a person in the distance. In China, landscapes grew out of portrait painting, seen as valuable only in relationship to the human figures it contained. These North Korean pieces are different, in that they represent a landscape totally removed from human use, from human form, and one feels as if the artist, while painting these scenes, takes on a “superhuman” identity, restraining his own humanity to the highest degrees through the practice of detached euphoria. In these paintings the government somehow belongs to the land, with the terrain blessing and legitimizing those who stand upon it with a sense of grounding and “Korean-ness”. I feel that the addition of human form to these particular painting would some how corrupt their purity and scope, because they were meant to preclude man, to humble man, and to show man’s universal insignificance. It is an artistic philosophy where transcendentalism meets nihilism in a realistic embrace. After seeing these paintings, my feeling is that this artistic perspective could reveal the basic differences in the Korean and Chinese socialist ideals, which have become painfully obvious to both countries and to the world as of late. While one socialist system is valued in its relation to humanity, a backdrop for human endeavor, the other is kept as an ideal too pristine for human interaction, almost requiring the elimination of human concerns to retain its inherent cultural authority.

We all like to talk about mysteries, sometimes even if a good explanation exists, preferring instead to talk in the quantities of “if”. These paintings are the seeds for such imaginations, because the illustrate a kind of speculative and symbolic aspect that could only occur in the minds of masters so removed from the mainstream of art and philosophy that their naiveté becomes a singular and revealing perspective on the process of creation. If they do mean what I see in them, through my contrast of North Korean art with the historical forms of Korean society, and comparisons to the traditions of North Korea’s closest ally, China, then they prove that one can communicate a wealth of information about worldview and personal politics through such dry topics as mountains and rivers, tigers, lakes, and the occasional crane. They show that to what extent omission can delineate something new through trite historical forms, and they illustrate the human ability to escape pain and fear in the creation of symbols. They also fill in a blank that remains the greatest unknown element in our interactions with North Korea, which has always been, “What do the people of DPRK think?”

We are all intoxicated by the opiate of political faith and the cultural superiority in one way or another, and seeing these paintings helps me to see myself in contrast to these remote minds who expressed themselves with water, soot, and rice paper in far away Pyongyang. Their silent stares prompt me to ask myself heretofore-unthinkable questions about the validity of the western myths I believe and reflect in my own art. And I see that, like the paintings spread before me, human lives are lived and defined by ideals and ideologies that fade like brush strokes from black to white, and which in turn are labeled by others and placed in relation to their own shades of gray. Paintings that raise such lively inner dialogue and pose such rare questions have their own innate value, and have much to offer those interested in the art in our contemporary world.

William Boyd is the creative director of Yin Media, Ltd, is an avid collector of East Asian art, and a student of Chinese painting and calligraphy under Master Wang Huibao. He resides with four generations of his wife’s family, his wife and children, in Shanghai, China.