☰

Graceful and young the peach-tree stands

How rich its flowers, all gleaming bright

This Queen to her new home repairs

Chamber and house she’ll order right

Graceful and young the peach-tree stands

Large crops of fruit it soon will show

This bride to her new home repairs

Chamber and house her sway shall know

Graceful and young the peach-tree stands

Its foliage clustering green and full

This “Nation” to her good home returns

Her household will attest her rule[1]

The Dragon that Ate Himself

A strange legend was transmitted from the ancient Chinese on half-forgotten incantations cast into bronze vessels and upon scattered pieces of old bamboo scrolls. These pieces told the story of the first dragon and the nine sons that she bore of different shapes and powers. These sons divided the world, and the fifth son, a demon of tremendous appetite that appeared in a wolf-like form, ruled over primordial China. The Taoist histories say that this wolf-dragon ate everything in tremendous portions, and demanded human sacrifice of those who worshipped him. In his state of ever increasing hunger, he preyed upon himself, and destroyed his body by chewing himself to pieces, like Ouroboros, the snake in Western myth that swallowed its own tail. As an “immortal”, he could not die, and so he was doomed to become an insatiable, disembodied face whose hunger pains could never be filled. He terrorized the world by falling out of the sky to maul and kill men in the fields, and unable to swallow his prey he would screech away in uncontrollable hunger pains.[2]

This dragon’s name was “Taotie” (饕餮), and his iconography has been one of the most enduring symbols in the Chinese tradition throughout time, carved into walls to scare away evil influences, and holding the rings of doorknockers to scare off thieves and ghosts. Some older Chinese villagers still believe that demons are scared of the sight of Taotie, and that prayers to him will make one wealthy but will damn the soul of the worshiper to torment.

“Under Heaven there are three cruel demons, and cruelest is Taotie, the Appetite”[3]

The Shang Empire (1600 BC — 1046 BC)

Taotie’s name merely means “The Consumer”, and early China was ruled by his cult, literally a cult of consumption. Taotie became a unifying and foundational identity to an ancient Chinese tribe conquered all of its surrounding peoples, and his face adorned their flags as a totem. This symbol was pronounced “Shang”, meaning “Burner-Destroyer-Sacrificer”, and it is by this name that we know China’s first empire, the Shang Dynasty.[4]

The Consumer’s fierce gaze was cast on the cauldrons that were used in human sacrifice and in cooking meat for rituals, and his grinning jowls decorated the hilts of razor-sharp bronze swords, eager to drink the blood of sacrifices slain in his honor. The disembodied face smiled on all the treasures of the kingdom, and technology and luxury were universally inscribed with this uncanny motif. The fanged smile became a symbol for wealth and power, and “gave face” to the rulers, who led this cult as supreme consumers. Millions of slaves labored under the glare of Taotie during the years of the Shang, as they stripped the earth to mine metal with which they could cast bronze armor and vessels to be inscribed with “Face”, and cried out for freedom from the tyranny of “Consumerism”.

The Coming of the Lawgiver

“Nine at the beginning means: Hidden dragon. Do not act.” [5]

Then, one man walked into history and changed everything. He was an unassuming man, named Zhou Wen, a musician and poet, merely trying to recover his eldest son, a fifteen-year-old boy named Bo. Bo had been taken as a captive to the palace of Shang, and legend has it that he was so handsome that the Empress tried to make him into a “consort for the women”. Zhou Wen was a chieftain of a small confederacy of villages, called the Kingdom of Zhou, just beyond the reach of the Shang Empire, in present day Shaanxi and Henan Provinces. His grandfather had started the Zhou in knowing contrast to the Shang, which he considered decadent, and had taught his grandson the arts of divination, music, and writing that had been passed down from the Great Ancestor, Fuxi. Wen was not a great warrior or a wealthy king, and his appearance seemed comical to the Shang. Instead of granting the boy’s father’s request, the Emperor of the Shang, named Yin, cruelly killed Bo in presence of the whole court, partly out of jealousy for the boy’s influence on the women of his household, and partly out of spite for Zhou Wen. It was with this action that would ultimately doom the Shang, for this insignificant king of a backwater kingdom was armed with something that the Shang could not understand – he knew how to tell the future by divining the Will of Heaven.

“Nine in the second place means: Dragon appearing in the field. It furthers one to see the great man come”[6]

Emperor Yin imprisoned Wen and secretly fed him meat pies made of his son Bo’s flesh, gloating that this insignificant little man was tortured and fed unknowingly on his son. But legend states that Wen knew what the evil ruler was doing because of his prophetic abilities, but he had to eat what he was given so as not to reveal his powers to his son’s murderers.

This was not unusual cruelty, for legends state that the pleasure-loving Emperor of Shang constructed a pond of alcohol in his palace, in which he and his concubines (who legend says were demons sent by the gods to destroy him) would paddle around and drink to their heart’s content, eating shish-kababs of roasted meat hanging from trees planted on artificial islands. For further enjoyment, the Emperor also invented a giant bronze running-wheel, which turned over a fire; so that the court could watch slaves run, faster and faster as their feet burned on the gradually heating metal, and laugh when they fell into the fire to burn to death.

While locked in his cell, Zhou Wen drew on his family teachings and started to write what would become one of the most influential books ever written, “The Book of Changes”. In this great work he proposed that survival could only be insured by centering one’s self in change, which was the course determined by Heaven upon the creation, and that change governed chance in a constant process of eight steps, eight principles that could be divined through a simple game of “pick-up-sticks” (the symbols of the elements of change shown in broken and unbroken yarrow stalks thrown on the ground). In turn, each of these principles could be contextualized by decisions and actions that would flow with the inevitable change, submitting to the Will of Heaven. Zhou Wen encouraged himself with the belief that if he could center himself in the ebb and tide of the swirling universe around him, enough to understand and take advantage of patterns that would emerge to his perceptive mind, he could wield entropy as a weapon and destroy the invincible Shang Empire. Although Wen was kept in prison for five years, seemingly helpless to change his circumstances, Confucius later said, “Zhou Wen, after his imprisonment could only say ‘it was good for me’, and thus we can see that good often comes from bad.”

“Nine in the third place means: All day long the superior man is creatively active. At nightfall his mind is still beset with cares. Danger! You are not to blame for what happened.” [7]

Then, unexpectedly, Zhou Wen’s people procured his freedom by amassing a ransom large enough to buy back their beloved leader, and in the Shang’s absolute arrogance, the emperor released Zhou Wen to return home. The Shang undoubtedly saw nothing one man could do to destroy the lifestyle they had grown accustomed to, and so Emperor Yin made his second great mistake.

“Nine in the fourth place means: Wavering flight over the depths. You have no blame for what happened.” [8]

Seeking Wisdom

“…If you use the family, the smallest unit of society, to gain the state, you can acquire the state. If you use the state to get the world, you acquire the world.”[9]

When Zhou Wen returned to his home, he swore that one day he would destroy the Shang, but he did not amass an army or forge weapons, instead, he tried to establish his government according to the philosophy that formed during his imprisonment, built on the concepts of “equitable relationships”, “centering one’s self in change”, and “obeying Heaven’s Mandate”. His government would only succeed if it was predicated by his personal wisdom and virtue as a leader, and because he did not feel sufficiently prepared, he began the search for a master.

“Nine in the fifth place means: The dragon flies in the heavens. It furthers one to seek the great teacher.”[10]

After fasting and consulting the oracles, he determined that he would be able to find a teacher in a remote part of the country, where he would be fishing. Zhou Wen went out with his companions to that area, and found that an old fisherman was indeed sitting on the riverbank, with long cane pole in hand. Wen started the conversation with the old man by asking the question, “Do you enjoy fishing”, to which the old man responded with the answer, “Fishing is like ruling a kingdom – trying to get good people to follow you is like trying to catch a big fish with a baited hook.”[11] The old sage answered the question with the answer that he was seeking, and without so much as asking him his name, Wen asked him to be the high counselor to the Zhou.

This master’s name was Jiang Ziya, and his position, as tutor to Zhou Wen, would prove one of the most fateful in history. For this old man, out of the wealth of his knowledge and genius in agriculture, business, government, and forgotten history, taught Zhou to rule the great through the small, and taught him to see the task of running the country as a process of managing family relationships. Protecting the family and establishing the village accomplished more than waging war ever could to defeat one’s enemies. Unbreakable loyalty for the ruler could be created if the ruler would resist the temptation for personal enrichment and give fair wages to provide for the ruled. Personal virtue could be cultivated by attending to the basic needs of people for marriage, family, land, and protection from enemies and natural disasters. If a government could provide these things, it would be like Heaven and the people would be like the earth, and the Mandate of Heaven would be carried out through the virtues of the government.

“When one protects the security of the people and produces profit for the people, he observes the laws of nature and statecraft.”[12]

In accordance with these principles, King Wen gave each family two Chinese acres for personal use, outlawed alcohol and idleness, and established the villages as self-governed units for the protection and benefit of the clan. Declaring all slaves and bondservants that escaped from Shang to be citizens of Zhou, he also gave them land to farm so that they could provide for their own needs, only requiring a small grain tax from all citizens to support the government in return, farmed at the center of each village by joint labor.

The Exodus into the Promised Land

The news of this generosity quickly encouraged thousands of slaves, commoners, and even lesser nobles of the Shang to desert and declare their loyalty to Zhou, which quickly bolstered Zhou’s ranks. They brought with them the collective memory of the country that had sacrificed them for the comfort of the ruling class, bringing the knowledge of bronze casting and weapon making with them. The Zhou government’s goodness, Jiang Ziya’s wise counsel, and King Wen’s ability to communicate with Heaven enraptured them and ingratiated the new citizens of Zhou. They rallied around King Wen’s vision and dedicated themselves to the building of a nation that would make a better life for generations to come. In order to provide land for all the new immigrants, King Wen ordered the settling of new villages in uninhabited land, and his government quickly expanded accordingly.

The Zhou’s flag and totem was created in opposition to the concept behind Taotie’s face. The Shang’s “Consumer” was contrasted with King Wen’s concept of the “Producer”, which was summed up by the picture of a “field” (田) in which “men” (“〡”or “人”) are “working”. It shows both the value of land and of labor in the Zhou philosophy of government. This character has evolved into a different form today (周), and is the Chinese symbol both for King Wen’s family name and the concept of “completion”. Millions of Chinese descendants carry this family name today.[13]

The Father and The Son

King Wen succeeded in raising his sons to continue his legacy[14] – a generation of famous warriors, farmers, and strategists. His second son, Prince Wu, after the death of his elder brother, became the crown prince of Zhou, while his third son, Zhou Gong, became a great philosopher and general. Wu quickly became a wise and capable ruler under Jiang’s tutelage, and the young man made the realization of his father’s goals of destroying the Shang and establishing an equitable government his motivations in life. He married Jiang’s daughter, who was as wise as her father, and they bore many grandchildren for King Wen in his old age. The king and the prince shared a common love for the Qin, an instrument that was handed down from Fuxi, and they added two strings to the instrument’s design to increase its upper and lower range, which would forever afterwards be called the Wen and Wu strings. Together, they wrote many poems, composed many tunes, played the strategy game of “Go” (围棋 “Weiqi”), and shared a relationship that would become the pattern for a thousand generations of love and mutual respect between father and son. The names “Wen” and “Wu” became ceremonial titles at many imperial coronations, invoked in the hopes of a successful, cross-generational relationship such as theirs.[15] Thus, the ideal of the “Sage King” blossomed in the Zhou family, and would project its influence into every aspect of the East Asian psyche and over every generation.

King Wen’s “One Hundred Sons” in an Anonymous Song Dynasty Fan (百子图)

Death Before Victory

King Wen died of old age, without seeing the fall of his rival. The whole country observed three years of mourning for their beloved emancipator. While he lived, he was a great example of a lifetime learner, teaching others that the first requirement for leadership is a willingness to change, “to center one’s self in virtue”, and to value the development of personal character above all other treasures. His death amplified his influence, and his principles were soon felt, not only in connection with his personal story, but also in what it meant to be a citizen of Zhou. He left behind a lasting testament in the form of two great accomplishments – a sustainable village based on small-scale farming, and a book that transmitted his philosophy of life. King Wen’s great dream was to comprehend the change that flowed from the Divine, to change with it and bend to its course, and thus receive the “Mandate of Heaven”.

Wen left his sons with a great task…

“It is a question of a fierce battle to break and to discipline the Devil’s Country, the forces of decadence. But the struggle also has its reward. Now is the time to lay the foundations of power and mastery for the future.”[16]

Prince Wu Slays the Dragon

“Nine at the top means: Arrogant dragon will have cause to repent.”[17]

After thirty years of Zhou building the quality of life for its citizen, Shang was severely affected by the population drain, and finally started to take offensive action against the Zhou. But, by this time, it was already too late. Shang had already been condemned as “corrupt” in the minds of the Shang’s commoners, many of which had relatives already living free lives in the Zhou kingdom. Each time the Shang sent their slave armies to battle the Zhou, large numbers of soldiers deserted to fight for Prince Wu. “Better to die a free man than to live as a slave” was the feeling that slowly collapsed Emperor Yin’s massive empire and established the Zhou.

While Zhou had grown exponentially over this time, it still covered a relatively small area in contrast to the Shang, and the Shang Lords had not felt threatened by the insignificant kingdom until now. With Zhou’s sudden increase of military might, the Shang felt that it was important to stop the upstart before any more harm was done to their state. The entire Shang army, legend states numbered over a million men, was called by the Emperor to wipe out the Zhou once and for all in the spring of 1046 BC.

Stormy weather hampered both sides from making decisive military moves as they came together at the valley of Mu Ye. For three days King Wu agonized over the fact that the inclement weather seemed to show Heaven’s displeasure, and made it impossible for him to carry out his father’s wishes to destroy the Shang. The old magician, Jiang Ziya, disagreed. Jiang said that if they used the weather to his advantage, allowing the Zhou soldiers to go without their armor, the freeborn soldiers in the Shang army would be at a disadvantage in the mud and rain with their heavy bronze trappings. Casting yarrow stalks in his upturned shield, King Wu saw the omens and ordered that his army carry out Jiang’s plan.

As the vastly outnumbered Zhou army of two hundred thousand charged the Shang camp, the sky turned as black as night, the thunder roared, and lightening struck the front line of Shang soldiers. Then Zhou soldiers cheered; Heaven was fighting on their side! The massive Shang army was struck with terror as they saw the white-clad Zhou soldiers charge through their camp with the flashes of lightening. The slaves in the Shang ranks turned on their masters and Emperor Yin’s nobles were quickly outnumbered and slain.

When the news of complete defeat reached the decrepit Emperor Yin, he ordered all his property to be brought into his court, his wives and concubines, children, servants, and slaves. There he ordered his soldiers to kill his family and then to kill themselves. Then the Emperor torched his golden palace and lit the lake of wine with the flame that had used so often to kill others for his own entertainment. As the fire licked around him and devoured his treasures, he sat upon his Taotie throne and laughed that the glory of the Shang would never fall into the hands of farmers and slaves.

“When all the lines are nines, it means: There appears a flight of dragons without heads. Good fortune.”[18]

The Ascension of the Saints

That day, the Zhou defeated the Shang, and the Shang army laid down its arms to accept King Wu as their complete sovereign. From this day onward, Wu would forever be known to history as “Wu the Great Ancestor”, the “Destroyer of Evil”. His victory and the miraculous events surrounding the battle only served to cement the concept of “Heaven’s Mandate” in the minds of the people, proving that King Wen’s revelations were true and the his philosophy of the “Sage King” was the qualifying prerequisite for rule.

The heroes that died at Mu Ye, on both sides, were memorialized in folk religion and supplied the pantheon of folk gods that Chinese worshipped for thousands of years to come. The fallen Zhou soldiers ascended to the embrace of the immortal ancestors Fuxi and Nuwa to populate the bureaucracy of heaven, and became saints to whom the farmers would pray for rain, ask for sons, and from whom protection was implored. The fallen Shang soldiers became the demons of Hell, torturing those who were evil enough to be sent there after death by the immortals in heaven.

The “Thousand-Year Reign” (1046 BC — 256 BC)

During the reign of Wu, the Zhou Empire spread over present day China and Korea, creating an empire of small villages – all based on the family and the ensuing, multi-generational clan, which was the “The Foundations of Power and Mastery” that his father had described. They were self-supporting, largely self-governing, and completely self-propagating, and linked to the empire through a commitment to the Zhou’s vision, the belief in the “Mandate of Heaven”, and their own desire for survival and protection. With a minimum of taxes and military obligations, the empire grew organically, as families grew under the favorable laws and colonized land on the edges of the wilderness.

Very little happened to the Zhou for the next 790 years, the longest continuous reign in human history, until it was eventually destroyed by its own success. After nearly a thousand years of upholding King Zhou’s ideas of simplicity and righteous governance, later generations of the Zhou clan grabbed increasingly larger powers to enrich themselves from the operations of state. Their lifestyles grew to resemble those of the Shang that Zhou Wen had condemned and had denounced as the reason for their necessary destruction. Unconcerned with history and unwitting of the dire consequences, the Zhou family brought back a familiar motif to show their proper place as luxuriant consumers… “In the end of the Zhou dynasty, the cauldrons were again covered with Taotie’s head… This teaches us that good and bad actions do not go unrequited.”[19] And just as their great ancestor prophesied, the Zhou ended shortly thereafter, to start another cycle of change according to the Mandate of Heaven.

Chinese philosophers and poets would forever look back on the Zhou Dynasty as their ideal, a unique instance of beauty and culture in a world otherwise full of barbarism. It was this sincere belief in Zhou’s golden age that inspired them to imagination, to imitation – the vision that caused them to study, to paint, and to play. It was the search for the “Will of Heaven” through the winds of change that formed their views of the mind, the family, the cosmos, and governance. Chinese throughout history would revolt against evil and injustice in remembrance of the Shang, and formed dynasty after dynasty in the name of Zhou. It formed many of the common aspects of the Chinese, Korean, and Japanese cultures, and provided the basic archetypes of East Asian culture to the world.

But this is not the end of the story. This was just the beginning.

DECADE OF KING WEN[20]

The royal Wen now rests on high,

Enshrined in brightness of the sky.

Zhou as a state had long been known,

And Heaven’s decree at last was shown.

Its lords had borne a glorious name;

God kinged them when the season came.

King Wen ruled well when earth he trod;

Now moves his spirit near to God.

A strong-willed, earnest king was Wen,

And still his fame rolls widening on.

The gifts that God bestowed on Zhou

Belong to Wen’s descendants now.

Heaven blesses still with gifts divine

The hundred scions of his line;

And all the officers of Zhou

From age to age more lustrous grow.

More lustrous still from age to age,

All reverent plans their zeal engage;

And brilliant statesmen owe their birth

To this much-favored spot of earth.

They spring like products of the land–

The men by whom the realm doth stand.

Such aid their numerous bands supply,

That Wen rests tranquilly on high.

Deep were Wen’s thoughts, sustained his ways;

His reverence lit its trembling rays.

Resistless came great Heaven’s decree;

The sons of Shang must bend the knee;–

The sons of Shang, each one a king,

In numbers beyond numbering.

Yet as God spoke, so must it be:–

The sons of Shang all bent the knee.

Now each to Zhou his homage pays–

So dark and changing are Heaven’s ways.

When we pour our libations here,

The officers of Shang appear,

Quick and alert to give their aid:–

Such is the service by them paid,

While still they do not cast aside

The cap and broidered axe–their pride.

Ye servants of our line of kings,

Remember him from whom it springs.

Remember him from whom it springs;–

Let this give to your virtue wings.

Seek harmony with Heaven’s great mind;–

So shall you surest blessing find.

Ere Shang had lost the nation’s heart,

Its monarchs all with God had part

In sacrifice. From them you see

‘Tis hard to keep high Heaven’s decree.

‘Tis hard to keep high Heaven’s decree!

O sin not, or you cease to be.

To add true luster to your name,

See Shang expire in Heaven’s dread flame.

For Heaven’s high dealings are profound,

And far transcend all sense and sound.

From Wen your pattern you must draw,

And all the States will own your law.

[1] Zhou Wen, “In Praise of the Peach Tree”, from “The Book of Songs”, translated by James Legge and adapted by the Author

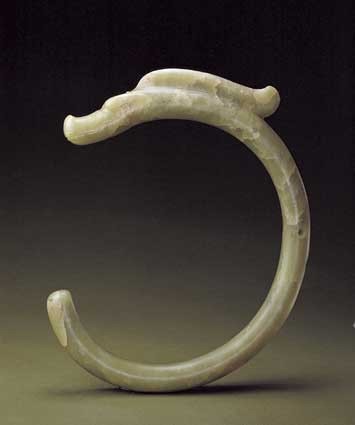

[2] The Hong Shan Dragons (红山龙 often called “Pig Dragons” 猪龙) were discovered in Liaoning Province in 1978, and are the oldest known jade object in China, dating back over five thousand years. They depict dragons eating their tails. Liaoning is important in the cultural origins of both the Chinese and the Koreans, and both had cities in this province over the 3,000 years of their recorded histories. The stories of the Taotie’s origin are found in “Records of the Evil Dragon Horse Hall” (怀麓堂集) from the Ming Dynasty, and in Xu Yingqiu’s “Recognition of Heavenly Fates” (天禄识余). It has been proposed by modern scholars that Taotie is a manifestation of the Sun God (太阳神) worshiped by many minorities in Southern China, and still referenced in the exorcism rituals of Nuo Opera, who is depicted only as a fanged mouth surrounded by fire. They believe that this deity could have meshed with dragon legends in the Shang Dynasty to create the explanation for Taotie’s existence. However, it is more probable that the literary record is accurate, and that the non-literary cultures of Southwestern China are reflections of it, rather than vice versa.

[3] “Ancient Inscription”, repeated by The Han Histories (汉书), in the “Chronicles of the Fifth Emperor of the Han”

[4] Some Western scholars insist that the “eyes” of this totem are really “stars” because of the Shang association of their Dynasty with astrology – this view is, however, not significantly substantiated in the tradition in the opinion of many Chinese scholars.

[5] Zhou Wen, “First Translation of the Heavens” from the I-Ching, adapted from Richard Wilhelm by the Author

[6] Zhou Wen, “Second Translation of the Heavens” from the I-Ching, adapted from Richard Wilhelm by the Author

[7] Zhou Wen, “Third Translation of the Heavens” from the I-Ching, adapted from Richard Wilhelm by the Author

[8] Zhou Wen, “Fourth Translation of the Heavens” from the I-Ching, adapted from Richard Wilhelm by the Author

[9] Jiang Ziya in conversation with Zhou Wen, “The Civil Strategy” from “The Six Strategies”, Translated by Nie Songlai in the Library of Chinese Classics Edition, Hunan People’s Press, pp 9

[10] Zhou Wen, “Fifth Translation of the Heavens” from the I-Ching, adapted from Richard Wilhelm by the Author

[11] From the beginning of Jiang Ziya’s “Six Strategies”, translated by the Author

[12] Jiang Ziya in conversation with Zhou Wen, “The Civil Strategy” from “The Six Strategies”, translated by Nie Songlai in the Library of Chinese Classics Edition, Hunan People’s Press, pp 11

[13] Or the derived family name, “Wang” (王)

[14] Legend says that he had one hundred sons, which led to the canonization of Zhou and his wife as “Bed Saints” by later Chinese villagers, and is possibly linked to the East Asian association that having male children is a reward for “righteousness”. These one hundred sons would later become the basis for the great houses of China, and the mythical origin of the “The Old One Hundred Names” (老百姓), the Chinese term for the families of China and the generic term for “commoner” or “peasant”. The Ming Dynasty work “Origins of the One Hundred Names” (百家姓) references the founding of the Zhou Dynasty more than any other historical event.

[15] These names also were used to describe two kinds of personality – “Wen” for the introverted student, and “Wu” for the extroverted man of action.

[16] From the I-Ching’s “Last Trigram – Wei Chi” by Zhou Wen, Translated by Richard Wilhelm

[17] Zhou Wen, “Sixth Translation of the Heavens” from the I-Ching, adapted from Richard Wilhelm by the Author

[18] Zhou Wen, “Seventh Translation of the Heavens” from the I-Ching, adapted from Richard Wilhelm by the Author. The symbol of a flying dragon, here symbolizing the founding of a great nation, would become the totem of the Imperial House, and would become one of the main symbols for the Chinese culture.

[19] “First Knowledge”, “The Spring and Autumn of Lu Buwei”, translated by the Author from the modern Chinese edition of the ancient text found in the Library of Chinese Classics, Hunan People’s Press

[20] From “The First Decade” in “The Book of Songs”, translated by James Legge